Hearing loss in the classroom

Hearing loss in the classroom

It is estimated that between 6 – 10 percent of New Zealand school children have some type, and degree, of hearing loss. The rate could be much higher as the reported incidence of hearing loss from health care professionals and the new entrant screening programme (which tests the hearing of all new school entrants) are not compared. There is also no record of the number of children who fail the initial screening test who go on to have a hearing loss confirmed. A study in the United States, found that 15 percent of school aged children had minimal hearing loss, or worse.

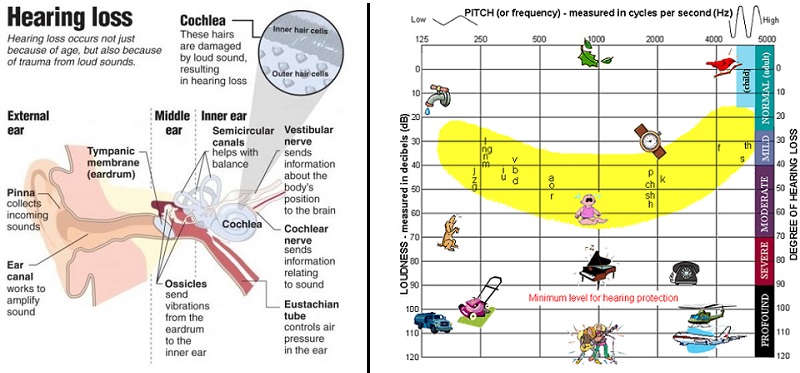

What is “minimal” hearing loss?

Normal hearing for children is 15 decibels hearing level, or better, at all frequencies with normal middle ear function. All else is abnormal and places a child at risk for academic failure. Because the normal hearing boundary for children is up to 15 decibels hearing level and a mild hearing loss is typically considered to start at 25 decibels. Most people define a minimal or slight hearing impairment as one that occurs from 16 decibels to 25 decibels hearing level. However, most hearing losses do not have a flat configuration. They have a slope. Therefore, a hearing loss may be minimal at some frequencies and worse, or better, at others.

The dictionary defines “minimal” as the least possible degree or quantity. Unfortunately, the term erroneously implies that the problem is insignificant. Implicit in the term “minimal” is permission to provide the least possible intervention and the fewest management strategies. However, children with minimal hearing losses experience problems in the following areas.

Minimal hearing loss in the classroom

In classroom situations, children with a hearing loss can find it particularly difficult to perceive speech due to poor listening conditions. A loss of greater than 16 decibels hearing level can result in a child missing more than 10 percent of a speech signal when the teacher is at a distance greater than 1 metre. The result?

- A child could miss subtle conversational cues that could cause them to react inappropriately

- Following fast paced verbal exchanges is difficult and dialogue may be missed

- A child may also not hear the fine word-sound distinctions that indicate plurality, tense and possessives

In addition, a child with a minimal hearing loss may appear immature and become more fatigued than normal hearing class mates because of the extra effort needed to hear.

Unfortunately, when teachers or parents notice attention and behavior problems, they often do not consider hearing loss as the source of a child’s problems.

In mainstreamed classrooms, hearing and listening is the cornerstone of the educational system. If a child cannot clearly hear the teacher, the entire premise of the educational system is undermined.

When a child cannot see well a teacher will often move that child to the front of the classroom. Moving a hearing impaired child to sit closer to the teacher is not an effective solution. This is because noise levels in classrooms can vary tremendously throughout the day depending on such factors as another class outside, windows open or shut, lights humming, not to mention the noise a roomful of children make. And don’t forget the teacher is not nailed to the floor. He or she often will walk around the room when teaching. Unless all children with hearing impairment can remain very close to the teacher, at all times, they will not receive a consistently intelligible speech signal.

Difference between “audible” sounds and “intelligible” sounds

It is important to note that there is a big difference between an “audible” sound and an “intelligible” sound. Speech is audible, if the person is able to detect its presence. However, for speech to be intelligible, the person must be able to understand what is being said. The major problem with hearing loss is that a child just cannot hear so well. Consequently, speech might be very audible but not consistently intelligible to a child with a minimal hearing loss. And this is the reason why, if a child is asked, “Can you hear me?” they are more than likely to answer “yes”.

It is also no solution to the problem for teachers to talk more loudly. An analysis of acoustic phonetics shows that when someone speaks loudly, vowel energy is increased, but consonant energy is not increased to the same degree. Thus, ironically, loud speech or yelling increases audibility but it may decrease intelligibility! So, a child might hear more sound from a loud-spoken teacher, but understand fewer words.

Poor acoustics exist in New Zealand classrooms

Schools in New Zealand remain largely unaware of this problem as evidenced by the poor acoustic standards found in classrooms. Studies have shown that only four to six percent of New Zealand classrooms meet national acoustics standards, allowing children to hear adequately. Hard surfaces, such as glass, concrete and lino, cause sound to bounce around and create echoes, increasing noise levels. This results in the cafe effect.

Schools in New Zealand remain largely unaware of this problem as evidenced by the poor acoustic standards found in classrooms. Studies have shown that only four to six percent of New Zealand classrooms meet national acoustics standards, allowing children to hear adequately. Hard surfaces, such as glass, concrete and lino, cause sound to bounce around and create echoes, increasing noise levels. This results in the cafe effect.

When the children are working in groups, someone will be talking loud so you talk more loudly to compete with them. Children lose concentration if they cannot focus on what they are being taught. Simply put, if they can’t hear, they don’t learn.

How teachers can help

It is essential that teachers identify who in their class struggle with audio delivery. This may be done with a series of listening tests.

There are a number of strategies that teachers may use in the classroom to assist hearing impaired children:

- Verbal instructions should also be reinforced with visual instructions

- Take the time to repeat instructions to that child one on one when the rest of the class is engaged

- Don’t be afraid to move around the classroom in a way that ensures you are standing close to a suspected hearing impaired child when giving critical instructions – and always back these up with written information, either on the board, or via a separate handout

- Classroom management is absolutely essential. Do not speak over the top of anyone. Insist on complete quiet before talking to a class and allow only one student to talk at a time

- Teachers should also get in contact with parents – let them know that a child should be tested for hearing loss. Hearing ability, like eyesight, does not remain constant throughout our lifetime

What parents can do

If your child’s teacher or school has concerns about your child’s ability to hear well, get your child assessed as soon as possible. If your child’s hearing tests come back as normal you should explore further the possibility that your child may be affected by an Auditory Processing Disorder.